Mortgage Affordability – 2005 Revisited

About 17 years ago (back in 2005) when mortgage interest rates were around 6% I posted an article called How interest rates can drastically affect real estate prices. At the time I was already amazed by the low interest rates and was concerned they would go up and how it would affect people. It’s finally started to hitting us, and what’s even more challenging is that the percentage increases per 1% is higher than it was in 2005 because interests are so much lower today than back then. In other words going from 6% to 7% is an increase in monthly payment of about 10% whereas going from 3% to 4% is an increase of between 13% and 14%. In fact at the time I hadn’t even calculated below 4% because I never thought it would go that low because that was below the historical inflation rate. We definitely live in different times.

In the last few months we’ve just gone from 3% to about 6%. I’m going to use 30 year fixed interest rate because it’s a lot easier as I can just use the FRED data. In any case that’s a 3% increase in a matter of months. That’s also double the interest rate! Looking at the chart from my previous article about how interest rates affect real estate prices, someone who could afford a $1000/mth mortgage back in the summer of this year could afford up to about $235k mortgage whereas today that translates into a $167k mortgage. That’s a huge drop of about almost 29% affordability. If you look at the median house price across the US of $429k (as of early 2022) then that means a drop of $124k, or a drop from $429k to about $305k. That’s very significant.

That was at the time while the market was hot and people were buying. What happens today when people are struggling financially and buying is much much lower? Where you just can’t flip your house or refinance on a higher valuation? If you look on Reddit there are a lot of stories of people on variable interest rates seeing large increases in their monthly mortgage payments. We’re talking multiple hundreds a month to over a thousand dollars more per month. That hurts.

Let’s do the reverse and let’s calculate the difference in monthly payments on a mortgage that was previously paying $1000/mth at 3% interest. We’re still going to use the 30 year fixed mortgage but the math still applies to variable rate mortgages as well as people who need to refinance. That being said a $1000/mth mortgage at 3% affords you a mortgage amount of about $235k. If we take that same $235k and apply a 6% interest rate then the payments balloon to a little over $1400/mth a month for a 40% increase in your monthly payments.

If we extrapolate that to the median house price (assuming 0% down to make the math easier) then that means a mortgage of $429k with a monthly payment of a little over $1800/mth. Today that has now exploded to $2572/mth for an increase of $772/mth. That’s very significant for the vast majority of people. That’s an increase of almost 43%! It’s not just the percentage but the absolute amount of $772/mth is by itself very significant considering the annual median household in the United States is $70,784 (as of 2021). That’s an increase of over 10% of their salary going to their mortgage. And that’s before taxes! If you do the math after taxes it’s probably 15-20% and higher. Ignoring that the median income generally cannot afford the median house, but if it could then the math would be even more challenging.

And we haven’t even started to touch on the topic of those mortgages which keep the monthly payments the same but add on the difference in payments to the mortgage amount. Meaning that if your monthly payment was suppose to go from $1000/mth to say $1400/mth than that $400/mth difference just gets tacked onto the principal amount. Meaning each month your principal is very likely increasing. For a median house that’s an additional $772/mth increase to the mortgage. It won’t be exactly that because of the details but it’s quite significant nonetheless. In other words they would be getting more and more into debt. What happens when they refinance when the mortgage term is up?

And that’s the key. The fallout will take some time to happen. There’s a lot of complexity and variables but there will be a correction, the question is more of when exactly. The first question is what is the average term of mortgages these days. In other words when are most people due to refinance? Until it comes time to refinance a decent amount of people will be able to muddle through. Not everyone but a lot. But once refinancing hits that’s where it will be very challenging for a lot of people. Especially if interest rates continue to climb as is expected to fight inflation. Yes we’ve pushed back inflation a little bit but I don’t believe that battle is anywhere near over. The other question is how many are on variable rates that can continue to holdout.

In addition as interest rates climb prices of houses have to fall. Prices were so high because affordability was so high because of the historically low interest rates. Aka free money. But in turn when interests go back up that also means house prices will have to drop which in turn means for a lot of people their equity will be decreasing. Instead of refinancing to take out equity of their property they will have to put in balloon payments if they end up being underwater. Can they afford that difference?

The other question is will inflation continue to be higher than interest rates because if it does then that could help out a lot people. So for example if inflation were to be at 10% (an even number) then assuming you had a 10% raise and the interest rate on your mortgage remained at the current 6% then you would actually be ahead. That mortgage would be worth less in 2022 dollars. As a more extreme analogy imagine a $30k mortgage for a house in 1980. $30k today is a much smaller amount then it was in 1980 and would be much more manageable then the median $429k. Of course it won’t be as extreme but when inflation is higher then interest rates it can be challenging. Even more so if salaries rise with inflation, which unfortunately doesn’t seem to be the case right now. Nonetheless inflation is having an impact on mortgage affordability.

Seeing as the goal of the Fed is to keep inflation rates in check I believe they will have no choice but to continue raising interest rates until inflation starts to go down, at least in the short term. At the very least keeping it higher then we’ve been used to for many years until inflation starts to get more reasonable. And that’s relative, even today’s “high” interest rates should be considered historically low interest rates. Pre-2000 interest rates were pretty much always above the current rate of 6%. The real question is how will this all play out in terms of interest rates and inflation as they both have very big impacts on loans and mortgages. The speed and scale at which they are moving doesn’t give the markets the chance to easily absorb the changes. This is leading to a lot of chaos and distress right now.

On a positive note there will be a lot of buying opportunities in the near future for those who position themselves well. Even with all the doom and gloom, or in fact because of the doom and gloom, there will be some great opportunities. As the saying goes, fortunes are made and lost in times of chaos, and we are clearly heading in such a time. Not that 2020-2022 were easy times, I just suspect that 2023 will be more interesting in terms of the impacts interest rates and inflation will have on the markets (financial and real estate). We’re about to see the true costs of all the recent money printing and the long term low interest rates. The can was kicked down the road but we’re now getting near the end of the road and can’t really keep kicking it much further without risking high inflation which is a much bigger and worse problem. Some even speculate a once in a generation market crash, a super cycle if you will. Whatever happens the thing to remember is that when there is chaos there is always good opportunities for both failures and much much more importantly successes. May you be one of the successful stories of 2023!

Permalink to this article Discussions (0)

Why Does a Hammer Cost $5000?

We’ve all heard the joke, that the government will pay $5000 for a $5 hammer that you can buy at your local Home Depot. Is it true? Not really, but everyone does know that the government generally pays a lot more for almost everything than if they just went to their local stores and bought what they needed. Why is that? Why would anyone want to pay so much for everything? Especially in these economic times? And even more especially for higher priced products and services where the savings are larger.

The real truth, which most people don’t really want to hear, is that we’re all partially to blame. It’s as much our fault as the governments. And once you start to understand it from their perspective, you start to understand why they do pay too much for things. It doesn’t make it better or right, it just gives you an appreciation for why things are the way they are. And more importantly, why they probably won’t ever change.

So let’s look at the purchasing process, starting from the top, for anything above the $1000-$5000 threshold. The threshold where you need to start getting approvals before you can make any purchases. Where you can’t just buy it on your personal credit card and just it get reimbursed. And before I get going, please remember that this process is the same for purchases of $10,000, $100,000, $1,000,000 or more. The only difference is that they involve more people and layers, hence more bureaucracy and costs. So if you’re going to sell something to the government for more than $1000-$5000, the process quickly becomes complex and expensive and you almost have to increase it by an order of magnitude to cover your costs.

Now I hate this next statement, but it was only after going through it while working for a few government entities in my consulting days that I was fully able to appreciate why the government (and many large companies)have their hands tied. I was always on the side of “this is crazy and bureaucracy is insanely expensive for nothing” but eventually it was explained to me in a way that I got it. So here’s my attempt to help you have pity on the poor people you’re trying to help. Oh, and realize that most of these same people don’t get this, it’s never really explained to them, so please be kind. Many just end up working for the government their whole lives so they assume this is how the world works. You can usually quickly and easily tell those that have worked for the government and very large companies their whole lives. It’s not a bad thing, it’s just a different way of working.

The first thing to remember is that the government is public facing, so they can get in trouble for anything that goes wrong (whether it was a right decision OR a stupid decision). So the general philosophy is CYOA (Cover Your Own A**). To give you an example, if you say need a computer system for your team of 10 people, and you try to do it yourself, if you make any mistake whatsoever you’re personally in trouble. In my case when I worked for a specific government entity and I tried to do this, I was told if even just one computer was infected with a virus, one wasn’t fully patched (or even if it was fully patched), if anything at all happened, I would be personally responsible. Anything at all, data being lost, a power surge, anything, regardless if it’s my fault, someone else’s, or even an act of nature!

Also if I use a vendor and someone somewhere else is cheaper, or has a better deal (regardless of the quality), I could be in trouble if anyone outside finds out. If another vendor gets hold of this info, if a member of the general public sees a better deal anywhere else, etc., they can target me because I didn’t follow the correct process and procedures. And even if I have the best deal in the world, there are still potential issues. Basically I can quickly and easily be in for a world of hurt. I would lose all government protection and could be personally liable.

So what can the government do to alleviate this mess because no one wants to personally take on that kind of risk for the little reward you get. The project is a wild success, you get some taps on your back, you might move up in your career with a small promotion (and that’s a big maybe, many departments have strong tendency towards seniority), and so on. You might get some rewards, but they won’t be anywhere near the same as the risk. What exactly are the risks? You can be fired on the spot. So immediate loss of job. You might not be able to work for any government entity again, depending on your level. You lose all your benefits. If you had a pension, that’s going to be limited from now, or gone in the worse case. You could have legal issues, even criminally charged in some cases. The risks are large, compared to at best a promotion.

Which means that most people aren’t willing to do anything bold or stick out their necks because the risks to reward ratio just doesn’t make sense. So to resolve that, the government force everyone to go through approved vendors. If the vendor is approved, you can’t get in trouble, you can’t be fired, and so on. You’re no longer personally at risk. Ok, that’s easy. And if a vendor is approved it should be because their prices are reasonable and the quality is good. But here’s where it fails and gets all wonky. As soon as you do that, all kinds of people and vendors come out of the woodwork complaining about why it isn’t them and why it’s not fair, regardless of whether or not theey’re right. So now the government has to create further processes by which you can be approved otherwise the public cries foulplay.

You don’t see this in a private or public companies, but with the government it’s different because of who they are. It’s insane how many people complain about everything! And if anything isn’t “fair” (which most things aren’t, that why there’s competition and a free market), it will generally make the papers. So this creates a lot of process and work for everyone. It’s a mess. With companies you can just ignore the public because you’re a company, but with a government entity you don’t have that luxury. You are accountable to the people.

So now a process gets put in place for selecting vendors. Of course some people still complain some more. So tighter measures get added to the process. Suddenly the only vendors willing to do all the paperwork charge crazy expensive prices for everything because it costs them an arm and a leg just to get in. And this is with no promises of any sales, that must be done after you’re approved (and costs further money). You want a $800 computer, that’s $5000. $800 for the computer, and $4200 for all the costs to get in the system and the risks of not getting a sale in the first place.

And so here we are. The poor government worker is screwed into going through all these crazy and expensive processes because they have to for their own personal safety. The very people who scream loudly that this is insane and stupidly expensive are often the same people who created this mess in the first place. If at every corner every single one of my purchases are being scrutinized and I can be fired for anything (nevermind the potential legal issues), I won’t do anything. It doesn’t make sense for me to buy anything, even if the consequences are potentially terrible. Which then forces all the crazy processes and brings us to where we are today.

I’m personally not fond of how that world works but unfortunately I do understand it and was able to navigate through it when I was a consultant (it helps to understand it). That’s also why I will never sell software to that world. The risks for a vendor are just too high. As a company you have to invest a lot of money for the chance to sell to the government at inflated prices. Sure you will make a profit, but it’s not nearly as big as most people think because of all the costs associated in selling to the government in the first place. That $5000 hammer might only result in a profit of $500, but that’s only a 10% margin with a lot of risk.

The main draw for companies is that once you’re in, it’s relatively easy to stay in. Most companies aren’t willing to go through all the effort and cost. That and the government doesn’t like to change, even if there are better and more affordable solutions, because there is a lot of internal costs and efforts in changing anything. Change is not fluid, it’s hard and has a lot of inertia. And it can be vetoed at almost any step. So if you are fortunate to get in, you can be locked in for quite some time, which is where the real benefits and profits to vendors come in. That’s the gravy boat. Not the prices you charge, but the consistent and long term almost guaranteed revenues and profits for those lucky few.

So even if you do get into the system, good luck trying to find any real decision maker willing to make an actual decision on your product or service within a reasonable timeframe! That’s the hardest thing possible, at least from my personal experience for anything more than $1000. From the government employee side, it’s much much easier to ride on a big decision for months, even years, before ever considering making the actual decision because you can’t get in trouble for finding more information and doing more research. That and being undecided generally won’t get you in trouble compared to what making a wrong decision can cost you. So what happens is that it takes a while for anyone and everyone to get into some kind of consensus and make a final decision. Eventually someone or some department has a strong enough need to push a decision, enough to champion and push it through. But until then, the sales cycle will generally be months to years. At least once a decision has been made things usually move relatively fast. That’s relatively fast, and not private world fast.

To give you a further example to contemplate about, if I’m the person in charge of a project and I decide to take a risk and do something, even if it’s only a 10% chance it can fail, an 80% we collapse if I do nothing, and a 90% chance of success (so massive chances of winning and almost no downside, and if I do nothing we fail), if it does end up failing, my career is most likely over. Not only can I get fired, I could be in the news and so on. If I do nothing and it fails because of inaction, I’m not personally to blame and still get my pension and everything else. The motivation for me to do move forward and do the correct thing is badly aligned with my personal motivations and success. In the private world, if you don’t move ahead and get some successes, you’re not gonna be around long, so the motivations are better aligned. They’re not perfect, we obviously have some issues as the Occupy Wall Street Protests have shown, but at least it’s closer.

In other words there is little incentive to take any kind of risk, even when the odds are incredibly stacked in your favor and the downside is minimal. As long as there’s any potential downsides, which there always are, then it’s against my motivation to act. Unless I’m a go-getter willing to take the risks, don’t know any better, I’m naive, or I just don’t care, the only time I’ll make any decision is when I can no longer push it off. The culture is amazingly strong to avoid making any real decisions. And you can’t blame them. What would you do if you were in that situation? And remember that most decision makers are at higher levels, so they generally have quite a number of years invested in their careers, not to mention their pension plans, and everything else that comes with being a government worker.

And that is why a hammer will cost a government entity many times more than it costs in real life. It’s a vicious cycle where you can’t blame the person who has to make the decision. Pay a realistic amount and PERSONALLY take on any and all of the risks and liabilities yourself OR follow a process which significantly increases the cost of everything and protects you in the process. A process that was created to protect the government from overpaying is the very one that causes them to pay so much! It’s a real bad lose-lose situation. And as far as I can tell, there’s no real way, and definitely no easy way, to resolve this problem. Which is why I predict the government will continue to overpay for just about everything for the coming future. Hopefully some day we can find a solution.

Permalink to this article Discussions (5)

Groupon – Back to Crazy Company Valuations

Just when I thought we were finally over the craziness of obscene IT company valuations of the 2000 dot com bust, I see Groupon’s latest valuation. $15 billion dollars for Groupon? That insanity! And although Groupon isn’t the only one getting ridiculous valuations, it’s definitely one of the worse along with Facebook’s $50 billion valuation from Goldman this month.

So let’s look at some numbers. And I’m not even yet talking about revenues or financials, let’s just look at the recent valuations. There’s no way the company’s growth is in line with the growth of its valuations.

In April 26, 2010, it was valued at $1.2 billion. This is when they said they expected to make $100 million for 2010. Shortly after this, Google offered Groupon somewhere between $5 billion to $6 billion, which they turned down. This month, based on their latest financing round of $950 million, Groupon has a valuation of $15 billion. Yes, that’s right $15 billion!

All this from a company that was spun off as recently as 2007, that only really started its web presence in late 2008. Now I’m not saying you can’t make large amounts of money in that amount of time, but creating $15 billion dollars of value, it’s not very likely.

But before I get too ahead of myself, let’s look at some concrete numbers, just to make sure I’m not the one who’s out to lunch here. Initially Groupon estimated it would make $100 million for 2010. It now appears that this number needs adjusting and they will claim upwards of $350 million in revenues. This is really good news, and it does explain why there’s so much hype for this company. My congratulations to Groupon for that kind of growth, it’s amazing!

But before we get ahead of ourselves, we need to realize that not all of Groupon’s revenues is theirs. Remember that Groupon has to pay up to 50% to the merchants. That means that their real revenues are probably closer to $150 million. In other words, the stated revenues are highly inflated, because although it’s revenues it’s not really real revenues. Unfortunately that’s going to help them get better valuations, especially if they become a publicly traded company. Most people just aren’t going to take the time to determine exactly how a company earns it’s revenues, they just quickly look at the numbers (if that, many just go with brand names or the hype associated to the a company). If you’re interested in more detailed analysis of Groupon’s revenues, Paul Butler has written a really good article. His analysis is pretty thorough and I agree with his findings.

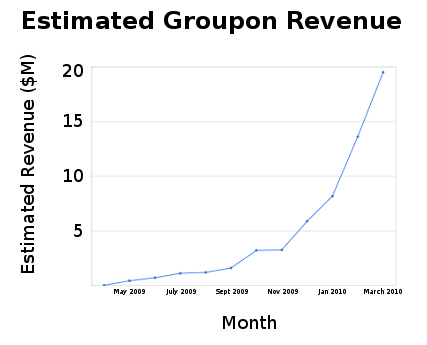

In any case, ignoring the issues with actual revenues, if you graph those revenues based on the available information, you get a revenue graph that pretty amazing (see below – source: Paul Butler). The growth curve is definitely something to write home about!

But even with that kind of growth, are the valuations worth it? Can it sustain that growth over time? Will the growth slow as the company grows? The bigger a company gets, the harder it is to maintain high growth levels. It’s much much easier for a $1 million dollar company to double in size than a $1 billion company. How often do $100 billion dollar companies double in size?

But most importantly, what is the premium paid for that growth today? In other words, how long do they have to continue that growth to get a reasonable valuation?

The best way to find out is to calculate the premium, for example using metrics such as P/E, and even that won’t really work because we don’t have enough information about Groupon (it’s a private company). But let’s go ahead and do a close enough comparison anyways, let’s do a P/R (Price / Revenue). Assuming my numbers are correct, that’s a P/R of about 43 based on total revenues. However if I make an adjustment to use their real revenues, the P/R skyrockets up to about 100.

Although we can’t do an accurate P/E calculation, we can do a quick ballpark calculation. Assuming 50% of that revenue goes to the merchant, we’re left with $175 million of revenues to make a profit from. Assuming another 50% for operating expenses (meaning a 50% profit which is very high and generous), that leaves us with $87.5 million in profits. Therefore as a quick ballpark, we’re looking at a P/E of 171 for Groupon!!! Is it just me, or is this P/E value all too reminiscent of the Dot Com Boom and Crash of 2000? And that’s just one metric. By the way, if we use a 35% cut rather than a 50% cut for the merchant, we still get a P/E calculation of 132. This is just as insane as 171.

And if metrics aren’t your cup of tea, maybe we can do direct comparisons of Groupon to existing companies with similar market valuation? Here’s a small list of companies valued similarly to Groupon.

| Company | Valuation | Revenues |

|---|---|---|

| Adobe | $17.03 billion | $3.8 billion |

| Best Buy | $13.93 billion | $49 billion |

| Staples | $16.83 billion | $24.2 billion |

| Symantec | $13.83 billion | $5.98 billion |

| McGraw-Hill | $11.54 billion | $5.95 billion |

| Groupon | $15 billion | $0.350 billion |

Do you know what the first thing I noticed in this list, not one of these companies has revenues below a $1 billion other than Groupon, or even several billion! Although I have to admit I haven’t done the most thorough search, I don’t think you’ll find many, if any, stocks with these kinds of valuations in the public market. The numbers just don’t make sense.

The premium on Groupon is such that you’re paying for it as though it’s already a very large and mature company. That is, the built-in premium on the company is so large that it would have to continue the same level of growth for at least a decade or more. The odds against that are extremely low.

I also believe every single company on the list above is worth more than Groupon. But don’t take my word for it, let’s look at another comparison. Let’s look at the valuation to revenue ratios. From our list above, the best (largest) ratio (other than Groupon) is from Adobe at 4.48. Groupon’s ratio is 42.85! That’s 10 times more than the best ratio on that list. If you can find a company that has even close to that ratio, that’s listed on either the Nasdaq or NYSE, then please let me know!

Using the 4.48 ratio, which is the best ratio (highest premium), that would make Groupon worth $1.5 billion. If we use the lowest ratio (Best Buy with a 0.28 ratio) that would make Groupon worth $98 million. Which means that Groupon should be valued anywhere from $100 million to a max of $1.5 billion according to this list. I agree the sample size isn’t very large, but this is a fairly common sample of companies at these valuations. As you get to valuations of this scale, the premiums start to diminish. It’s understandable for smaller companies that can grow faster, but at these scales it’s much more difficult to get similar growth rates for larger companies.

Anyways, do any of these companies really compare to Groupon in terms of value? If someone gave you the option of getting $x of stocks in only one of these companies, and you had to wait at least 3, 5, or even 10 years to sell, which company would you select? Is Groupon worth 10 times as much as those companies? I personally don’t think so. Do you?

Permalink to this article Discussions (1)

The Sunk Cost Effect

There are many many many many many books that teach you how to make money, but almost none that show you how to avoid losing your money. I personally had never really thought about this, at least not until I read the book What I Learned Losing A Million Dollars (an amazing book that I strongly recommend). Like everyone else, I was more concerned about making money rather than about how not to lose it. But as Jim explains it, there are many ways to successful make money but few to lose it all. You can invest in opposite strategies and still make money! The key to long term wealth is to understand the psychological forces that induce us to lose our money, even through our best efforts.

The book What I Learned Losing A Million Dollars starts off with Jim’s personal story of how he quickly climbed up the success ladder and then in a matter of a few months lost his entire wealth. What’s most interesting about the book is that what happened to him could happen to anyone. But the scariest part is how fast it can happen. It’s not that he did stupid things or spent wildly, it’s that he got caught up in a psychological trap. One that we all fall prey to from time to time, just on smaller scales.

Once it was all over for Jim, he went on a quest to find what the best investors did. What he found is that there was no consistency, they were all over the place. Many of them contradicted themselves and still succeeded. This lead him to question how this was possible, after all in most cases when two people use the opposite strategy one person has to come out ahead at the expense of the other. That’s how the markets work.

What he found out was that this wasn’t necessarily true. What happens is that successful investors know when to stop, when to drop an investment. Investors using opposite strategies aren’t always in the market, they’re in the markets at different times. They know when to wait on the sidelines until the markets favor their strategy. They don’t fall prey to as many psychological traps as ordinary people do. That is the only common thread he was able to find for highly successful investors!

And today we’re going to discuss one of those very common traps. It’s the effect of looking at your previous costs in determining whether or not to go forward today, otherwise known as the Sunk Cost Effect.

To give you a common example unrelated to investing, just to show how prevalent and strong this effect is, let’s take the example of car ownership. Let’s assume you own a car that’s a few years old (still pretty new) and you’ve just spent $2000 in repairs on it a couple of months ago. Suddenly this week it starts misbehaving, you bring it to the garage, and find out you need to spend another $1000, $2000, or even say $4000 on it. What do you do?

The best answer is to look at the value of the car TODAY and determine if it’s worth it TODAY. However, and this is where we almost all fall prey to the sunk cost effect, is that we also look at the fact that we just spent $2000 a couple of months ago. We’ve already spent that much money on it, so we might as well go forward with the new repairs. We don’t want to lose that $2000 in repairs from a couple of months ago. We may even rationalize that what we fixed a couple of months ago won’t break down again for some time so the car is better for it. And that’s a big problem!

What happens now if in another month we get another bill for another $2000? Well you have to get the repairs, after all you just spent $3000-$5000 in the last few months. And then what happens in another couple of months if it repeats. Oh my god!! We just spent $5000-$9000, there’s no way we want to lose all that money and/or effort. And so the vicious cycle has started and we start to lose more and more money just because we didn’t want to lose that initial $2000!! Trying to avoid losing that initial $2000 repair bill has now cost us around $10,000, and it’s only going to get worse! If the car is a lemon, how long will it take for us to give up? If you think it was hard at $2000, imagine now at $10,000! The more you lose, the harder it gets to pull out!

And it’s not just with cars, it can happen with just about anything. It can happen with your job. You may have already committed 3, 5, 10, 20 years to this job. You may hate it, it may be paid below market rates, and so on. But since you’ve already committed so much to it, you’re probably less and less likely to quit with time. This is why people get caught up in jobs they don’t like for years and years.

With investing, in real estate it could be you’ve already spent so much money renovating a property that you now have to wait to sell it until the market recoups, losing money each month for years and years, possibly losing everything through bankruptcy to avoid losing that $10,000 you initial spent on renovations. In the stock market, it’s a stock you bought at too high a price that you’ll now hold onto until it goes back to at least it’s original price. The list goes on and on.

The reality is that we should always look at whether something is worth it as of today. Period. It doesn’t matter how much time or money we spent on it in the past, we need to look at how much it’s worth today. If you can do that, you will save yourself a lot of trouble and money!

And that’s what smart investors do. They evaluate an investment in terms of what it’s worth today, they don’t look at how much they’ve already invested. In other words, you should always ask yourself: If I wasn’t already committed would I invest into this today? If the answer is no, then you need to seriously consider getting out of your investment before you fall prey to this trap, otherwise it will be that much harder as your position gets worse!

Permalink to this article Discussions (1)

How to Get a Pay Cut AND Be Happy About It

Let me start by asking which you’d prefer:

- A 10% raise?

- A 3% raise?

If you’re like almost everyone, the answer is hands down #1. But let me re-phrase the question a bit. Which would you prefer?

- A 10% raise in 1980?

- A 3% raise in 2009?

Is your answer still the same? I bet you think it’s a trick question because I added a year to the options. You’re right, it IS a trick question! The years 1980 and 2009 are special. Can you guess why? 1980 is very well known for having a very high inflation rate whereas 2009 is known for being a deflationary year (a year where the inflation rate is negative). In 1980 the inflation rate was 13.5% whereas in 2009 it was -0.4%. Having brought this new information to light, is your answer still the same?

In other words, which do you prefer:

- 10% raise at 13.5% inflation in 1980 = a real -3.5% raise in terms of purchasing power

- 3% raise at -0.4% inflation in 2009 = a real 3.4% raise!

Looking at the numbers adjusted for inflation, option #2 is now by far the best economical choice, beating option #1 by almost 7%!! Option #1 is actually a pay cut!

Now here’s the kicker, although most people realize option #2 is the best economically, the majority of us FEEL that the person in option #1 is HAPPIER with their raise than the person in option #2. Notice here I said feel happier, NOT that they were financially ahead! Although we’re able to differentiate between the two, most people still believe they would feel happier with option #1!!

What’s more, this same research paper (Money Illusion) also discovered that people believe the person in option #2 was more likely to leave their job. Basically, as William Poundstone summarized in his book Priceless, the overall theme of the paper is:

“$$$ = happiness = actual dollars NOT ADJUSTED FOR INFLATION”.

So how do you get a pay cut and be happy about it? Get a raise, but have that raise be less than the rate of inflation.

Permalink to this article Discussions (0)

As If We Weren't In Enough Trouble Already?

We all know the real estate market is in a mess right now, and most of it is really our fault. Too many people took on mortgages they never should have. But it’s not just the borrowers that are guilty, the lenders need to take their share of the blame. Obviously everyone should know when they’re over-extending ourselves, but in obvious situations many lenders still encouraged people to get mortgages. They often helped them get financing through more creative ways, such as loan/mortgage applications that didn’t require any proof of employment, interest only payments, 105% financing, and so on. I won’t even mention mortgages that required high and consistent capital appreciation just to be sustainable.

As part of this mess, many different sales techniques were used. A very common technique was focusing on how much mortgage you CAN afford per month (not how much you SHOULD afford per month). What this means is that instead of looking at the total purchase price, you focus on the monthly payments. By doing this, especially when interest rates are incredibly low, you end up buying properties that in any normal time is well above what you can afford. Which also means that when interest rates go back up, which they will, you’re in a lot of trouble!

Again, the benefit of this selling technique is that you can take the focus away from the real price and look at what you can spend each month. This gives the seller a lot of leeway in the price (not to mention it helps increase commissions). As an example, adding $2000-$5000 on a $500,000 mortgage amortized over 30 years (at our current historically low interest rates) barely changes the monthly total ($9/month and $22/month respectively)! Even adding $20,000 isn’t that big a deal. At 3.5%, $20,000 barely adds $90/month more. $90/month more on a $2500/month mortgage is not a big difference.

But, getting back to the reason for this post, is that lenders have now come up with a new method of rationalizing why you should purchase overpriced properties, or at least a method that I haven’t personally seen yet. Here’s the exert from Tales From the Real Estate Wars:

“Now’s the time to move up to a larger house and eradicate any loss on your present house! How, you say? Come a little closer and I’ll explain: If you bought a house for $350,000 and it is now worth only $280,000 (20% less), you have only “lost” $70,000 if you sit still and do nothing. But if you buy that really big house in the nicer community that used to be worth $550,000 and is now also 20% lower, the moment you close on that house at $440,000, you’ve gained $40,000 ($110,000-70,000). And hey, that’s before you get the $6,500 tax credit! Plus, have you seen how low the interest rates are?”

It’s really perverse logic, but at the same time I can see how people can fall prey to it. They’re focusing on people’s loss aversion fears which is a very strong emotion!

Do you see the flaw in the logic?

Permalink to this article Discussions (0)

Why I Have So Many Printers

I hate to admit it, but I have more printers than I have computers. Why is that? Is it because I love printers? Not at all. It’s because it’s economically cheaper to buy a new printer almost every time I run out of ink.

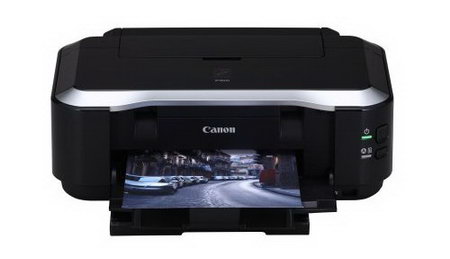

For example, today on Amazon I can buy the Canon iP3600 Inkjet Photo Printer for $43.08. Don’t be fooled by the sale price, just do an Amazon search for printers in the $25-$50 range and you’ll find lots of printers in that price range. Many are cheaper than this Canon printer, I just picked it because the discount wasn’t as heavy as some of the other models.

Now if we look at the price of ink cartridge to replace it, what they call the value pack, to replace all the colors including black, it comes to $41.05. Yes, it’s actually cheaper to buy a new printer than to buy ink. And I get a new printer!!

I understand that ink is where printer manufacturers make their profits, and that more often than not the printers themselves are loss leaders, but this is a bit ridiculous. Is it just this one case?

Epson has a WorkForce 30 Color Printer selling for $59.99. To replace the ink requires a $16.49 purchase for black ink and a $32.99 purchase for color ink. Combined, that’s $49.48, just $10 shy of a brand new printer!

And it’s not just Canon and Epson that do this, pretty much all printer manufacturers are in the same boat. Too often the price of replacing the ink is equal to or greater than the price of a new printer.

I do understand that the ink packs they give you with new printers aren’t the same size as replacements, but most people don’t generally think about this when they’re in the store itself making the purchasing decision. What we’re thinking is in the first case I get a free printer. In the second, for $10 more we get a whole new printer!

With this in mind, it’s easy to understand why people such as myself have too many printers.

And don’t get me started on how shoddy most printers are built these days. How many printers have you had that lasted more than a year or two before they stopped working?

PS: The prices on Amazon have already changed from when I initially wrote this post.

Permalink to this article Discussions (4)