The Sunk Cost Effect

There are many many many many many books that teach you how to make money, but almost none that show you how to avoid losing your money. I personally had never really thought about this, at least not until I read the book What I Learned Losing A Million Dollars (an amazing book that I strongly recommend). Like everyone else, I was more concerned about making money rather than about how not to lose it. But as Jim explains it, there are many ways to successful make money but few to lose it all. You can invest in opposite strategies and still make money! The key to long term wealth is to understand the psychological forces that induce us to lose our money, even through our best efforts.

The book What I Learned Losing A Million Dollars starts off with Jim’s personal story of how he quickly climbed up the success ladder and then in a matter of a few months lost his entire wealth. What’s most interesting about the book is that what happened to him could happen to anyone. But the scariest part is how fast it can happen. It’s not that he did stupid things or spent wildly, it’s that he got caught up in a psychological trap. One that we all fall prey to from time to time, just on smaller scales.

Once it was all over for Jim, he went on a quest to find what the best investors did. What he found is that there was no consistency, they were all over the place. Many of them contradicted themselves and still succeeded. This lead him to question how this was possible, after all in most cases when two people use the opposite strategy one person has to come out ahead at the expense of the other. That’s how the markets work.

What he found out was that this wasn’t necessarily true. What happens is that successful investors know when to stop, when to drop an investment. Investors using opposite strategies aren’t always in the market, they’re in the markets at different times. They know when to wait on the sidelines until the markets favor their strategy. They don’t fall prey to as many psychological traps as ordinary people do. That is the only common thread he was able to find for highly successful investors!

And today we’re going to discuss one of those very common traps. It’s the effect of looking at your previous costs in determining whether or not to go forward today, otherwise known as the Sunk Cost Effect.

To give you a common example unrelated to investing, just to show how prevalent and strong this effect is, let’s take the example of car ownership. Let’s assume you own a car that’s a few years old (still pretty new) and you’ve just spent $2000 in repairs on it a couple of months ago. Suddenly this week it starts misbehaving, you bring it to the garage, and find out you need to spend another $1000, $2000, or even say $4000 on it. What do you do?

The best answer is to look at the value of the car TODAY and determine if it’s worth it TODAY. However, and this is where we almost all fall prey to the sunk cost effect, is that we also look at the fact that we just spent $2000 a couple of months ago. We’ve already spent that much money on it, so we might as well go forward with the new repairs. We don’t want to lose that $2000 in repairs from a couple of months ago. We may even rationalize that what we fixed a couple of months ago won’t break down again for some time so the car is better for it. And that’s a big problem!

What happens now if in another month we get another bill for another $2000? Well you have to get the repairs, after all you just spent $3000-$5000 in the last few months. And then what happens in another couple of months if it repeats. Oh my god!! We just spent $5000-$9000, there’s no way we want to lose all that money and/or effort. And so the vicious cycle has started and we start to lose more and more money just because we didn’t want to lose that initial $2000!! Trying to avoid losing that initial $2000 repair bill has now cost us around $10,000, and it’s only going to get worse! If the car is a lemon, how long will it take for us to give up? If you think it was hard at $2000, imagine now at $10,000! The more you lose, the harder it gets to pull out!

And it’s not just with cars, it can happen with just about anything. It can happen with your job. You may have already committed 3, 5, 10, 20 years to this job. You may hate it, it may be paid below market rates, and so on. But since you’ve already committed so much to it, you’re probably less and less likely to quit with time. This is why people get caught up in jobs they don’t like for years and years.

With investing, in real estate it could be you’ve already spent so much money renovating a property that you now have to wait to sell it until the market recoups, losing money each month for years and years, possibly losing everything through bankruptcy to avoid losing that $10,000 you initial spent on renovations. In the stock market, it’s a stock you bought at too high a price that you’ll now hold onto until it goes back to at least it’s original price. The list goes on and on.

The reality is that we should always look at whether something is worth it as of today. Period. It doesn’t matter how much time or money we spent on it in the past, we need to look at how much it’s worth today. If you can do that, you will save yourself a lot of trouble and money!

And that’s what smart investors do. They evaluate an investment in terms of what it’s worth today, they don’t look at how much they’ve already invested. In other words, you should always ask yourself: If I wasn’t already committed would I invest into this today? If the answer is no, then you need to seriously consider getting out of your investment before you fall prey to this trap, otherwise it will be that much harder as your position gets worse!

Permalink to this article Discussions (1)

A Failed Experiment – And why It's Important to Measure Everything

For some time now I’ve been considering having a weekly post where all I’d do is list interesting blog posts, articles, news, etc. that I found online over the week. In late April I decided to go for it, and so was born the Lazy Friday Reading Assignments. These posts consisted each of a list of links with information around each link explaining why that link was interesting.

In terms of results, I mostly expected that these posts would have much higher clickthroughs than normal (because it’s a list of links to check out). I also thought that the overall traffic, and the subscriptions (Google Feedburner count), to the blog would continue it’s normal growth. And if I was lucky, other sites would learn about this blog and hopefully send additional new traffic.

The results were not what I expected! And this is why it’s important to measure everything.

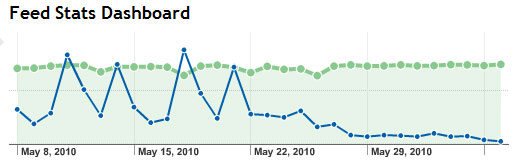

In the graph above, the blue line represents “Reach”, or as Google defines it, the number of people who have taken action on your content. I had 4 Lazy Friday Reading Assignments on the graph, and all 4 resulted in higher clickthrough days. There are actually about 8 posts in the timeframe of the graph, with the last post being on May 21st (I’ve been too busy over the last while to post). In any case, the end of the graph is the baseline with no posts (about 2+ weeks since my last post), the lower levels of the blue line on the left side are the baseline for normal posts, and the higher numbers are the Lazy Friday Reading Assignment post days. Exactly as I would expect them to be!

The traffic, as measured by unique visitors, did increase over this time, but not much more than my normal growth levels (it’s not displayed on the above graph, I measure unique visitors through other sources). This is more or less what I expected.

But, and this is a big but, the subscription count as measured by Google Feedburner (the green line), was not at all what I expected! Looking again at the graph above, you’ll see that while I was publishing the Lazy Friday Reading Assignments, the green line has dips and overall didn’t really increase. Although the dips don’t exactly correlate to the Lazy Friday Reading Assignment days, I can assure you it’s the first time I’ve ever seen this behavior (there’s also some delays with when Google Feedburner sends out the newsletter by email for those that subscribed by email). Normally when I write a post I’ll see an increase in subscription count on those days (the reverse). I would’ve included an example, but I wasn’t able to find a way to generate a graph from Feedburner for a specific date other than the last 30 days (the full length is too massive).

Although those dips may not look too big, they do represent a decrease of several hundred subscribers. This is significant enough! And more importantly, it’s consistent. During the experiment the subscription rate had absolutely no growth. There’s been more subscription growth with me doing nothing for 2 weeks after the experiment than during the whole month of the experiment!

In other words the experiment was a failure. Therefore the Lazy Friday Reading Assignment is no longer. Although I thought it was a good idea, this didn’t turn out to be the case. Which is why it’s a good idea to measure what you’re doing. Had I not had these metrics, I may have continued for a long time before realizing my error.

Which is why it’s important to measure, measure, and measure again.

PS: Looking at the graph also reminds me I should be posting more consistently.

Permalink to this article Discussions (2)